How to Break the Big Server’s Grip on a Match

How to Break the Big Server’s Grip on a Match

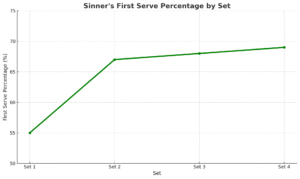

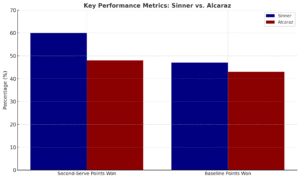

At this year’s Australian Open, Carlos Alcaraz and Elena Rybakina demonstrated how a dominant serve—especially when paired with a decisive serve +1 game—can dictate tempo and apply constant scoreboard pressure. Their opponents, Iga Świątek and Alex de Minaur, were often left reacting, unable to find traction as service games passed quickly and decisively.

After her win, Rybakina was clear: “Most important for me is to be focused on my serve, since it’s a big advantage if it works.”

The question is, what could Świątek and de Minaur have done differently?

Beating a big server isn’t just about returning well—it’s about constructing a return game that disrupts rhythm, accumulates pressure, and reshapes the match dynamic.

1. Disrupt Rhythm and Repetition

Big servers—and especially those who rely on serve +1—depend on tempo. Disrupting that rhythm narrows their comfort zone.

-

Adjust return position. Move forward on second serves to pressure timing; drop back to read pace and spin. Varying positions forces constant recalibration.

-

Vary split-step timing. Small shifts in timing can unsettle their toss or motion, making it harder to find rhythm.

-

Control tempo between points. Take your time after quick points. Routines help reset focus and interrupt momentum.

2. Pressure the Second Serve

Second serves offer the cleanest entry point to shift initiative.

-

Step inside the baseline. Early contact compresses their time and limits the setup for their next shot.

-

Target the body or corners. Jam them or stretch their court coverage to disrupt serve +1 patterns.

-

Prioritize depth. A deep return neutralizes the third shot and reduces their ability to dictate.

3. Make Return Games Cumulative

Breaking doesn’t happen in one point—it builds over time.

In my own playing days, I faced servers pushing 140 mph. My goal? Reach 4–4 in the second set with a message: I’ll get this return back when it matters. More often than not, that pressure produced the one break I needed.

Extend Early Games

-

Force more second serves

-

Reveal serve +1 tendencies

-

Increase cognitive load

Apply Consistent Pressure

-

Prioritize reliable, deep returns

-

Keep them from dictating early

-

Force decisions on the third shot

Neutralize the Three-Ball Sequence

-

Take away the short return

-

Use central, shaped returns

-

Extend beyond three shots—where execution becomes less certain

Return games are investments. When the payoff comes, it can decide the set.

4. Expose Movement and Transitions

Many serve +1 players excel in linear patterns. Ask them to move or transition, and their control often drops.

-

Change direction with depth. Crosscourt-to-line sequences stretch positioning and delay their ability to set up.

-

Bring them forward. Short slices test their footwork and decision-making in transition.

-

Use height and spin. High topspin—especially to the backhand—pushes them off the baseline, softening the serve +1 edge.

5. Manage Your Psychology

You will get aced. You will lose quick points. The match often turns not on those moments—but on how you respond to the next one. Stay composed long enough, and your opportunity will come.

-

Expect, don’t overreact. Treat aces and unreturnables as part of the job. They’re not personal—they’re neutral.

-

Stick to routine. Between-point habits help regulate emotions and reset focus. They anchor you when momentum swings.

-

Prioritize execution. Did you hold your return position? Did you hit your target? Did you disrupt their rhythm? These are your metrics—not just the scoreline.

-

Play the long game. Pressure accumulates. The longer you resist clean holds, the more doubt you create—and the more likely your moment arrives.

Wrap

Big servers thrive when they’re allowed to repeat serve +1 sequences uninterrupted.

Świątek and de Minaur—both strong movers and disciplined tacticians—found themselves defending more than constructing.

Turning that around requires clarity and intent:

Disrupt rhythm.

Pressure second serves.

Extend games.

Change the geometry.

Manage your mindset.

These aren’t shortcuts—they’re sustainable levers for long-term resistance. And against the modern power server, they might be your best chance.