The Science of Pain Management

The Science of Pain Management

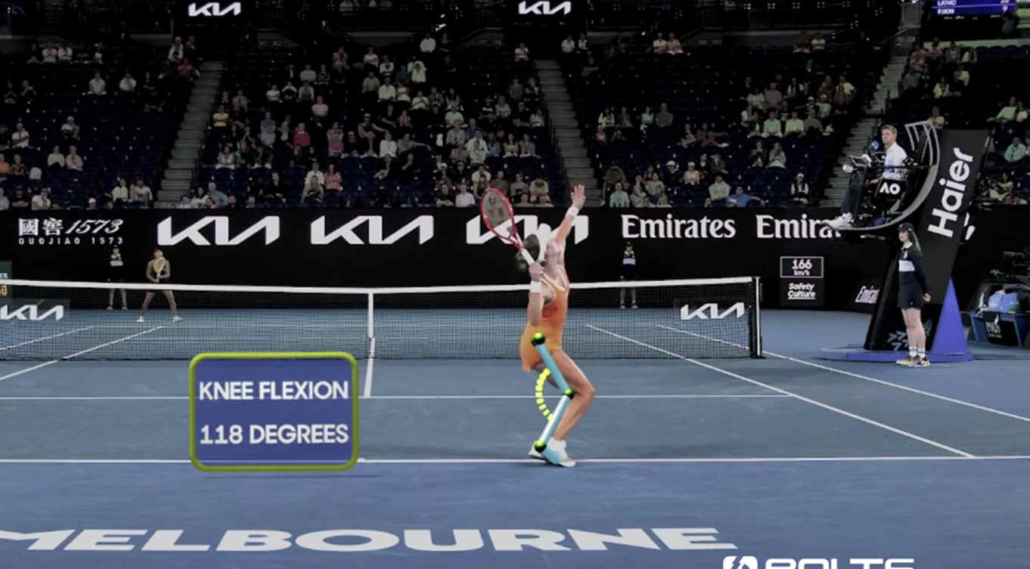

At the Australian Open, we witnessed a familiar scene: players pushing through injury, some barely moving between points.

For professionals, pain isn’t just a possibility—it’s part of the job. But how that pain is understood and managed is beginning to change.

In her new book, Tell Me Where It Hurts, pain psychologist Rachel Zoffness presents a broader view. Pain, she explains, isn’t just a signal from a damaged body part. It’s shaped by context—emotions, past experiences, and beliefs. In tennis, this matters more than we tend to acknowledge.

Pain Isn’t Always About Damage

One of the most useful insights in Zoffness’s work is also one of the most counterintuitive. She describes a construction worker who jumped onto a long nail that pierced his boot. He was in severe pain and required emergency treatment—only for doctors to discover the nail had completely missed his foot. In contrast, another man walked around for days unaware that a nail had lodged deep in his face, just millimeters from his eye. There was significant tissue damage, but very little pain.

The point isn’t anecdotal shock value. It’s a reminder that pain and injury are related, but not interchangeable. Pain does not function like a direct readout of tissue damage. Instead, it reflects how the brain interprets threat, safety, and context.

For tennis players, this has practical consequences. Pain may linger long after scans show healing is complete. Conversely, pain can flare suddenly without a clear structural cause. This doesn’t mean the pain is exaggerated or psychological in a dismissive sense. It means the brain is integrating multiple inputs—physical sensation, fatigue, stress, fear of reinjury, match importance, past experiences—and producing a protective response.

Understanding this distinction can change how pain is managed. Rather than treating symptoms as a simple sign of damage, players and support teams can ask better questions: What else might be contributing? What has changed recently—load, sleep, stress, expectations? Often, addressing those factors can reduce pain even when nothing “structural” has been fixed.

In short, pain is real—but it isn’t always a reliable measure of what’s happening in the tissues. Recognizing that gap is a necessary step toward managing it more effectively.

What This Means for Tennis Players

Players often manage pain with a narrow toolkit: rest, treatment, and medication. But Zoffness highlights other tools that are often overlooked:

-

Managing anxiety about the injury

-

Strengthening social support (teammates, coaches, staff)

-

Improving sleep quality and stress regulation

-

Adjusting internal narratives—moving away from “I’m broken” to “I’m adapting”

In other words, addressing the full system, not just the symptom.

Better Communication and Support

Rachel Zoffness emphasizes a critical but often overlooked component of pain management: language. The words we use—especially from figures of authority like coaches, physios, or medical staff—can significantly shape how an athlete experiences and responds to pain.

Statements like “your pain is permanent” or “you’ll have to live with this” can unintentionally amplify fear, reduce motivation, and even worsen symptoms. They reinforce a fixed mindset around injury, leading players to believe their condition is unchangeable and that pushing through is the only option. This can increase stress, which, in turn, feeds into the pain loop itself.

Coaches and support teams can play a major role in breaking that loop by using language that acknowledges the pain while also keeping the door open for improvement. Examples include:

-

“This type of pain is common in athletes and often responds well to rehab.”

-

“Let’s keep tracking how it changes—pain can shift, and we’ll adjust accordingly.”

-

“Pain doesn’t always mean damage; your body may just be signaling that it needs support.”

These kinds of statements aren’t false reassurance—they’re grounded in science and give the player a more accurate, flexible narrative.

Importantly, this shift in communication applies not only to chronic conditions but also to acute flare-ups during competition. A player nursing a sore wrist in a tournament doesn’t just need tape and ice—they need reassurance that the situation is manageable, and a plan that makes them feel in control, even if the symptoms don’t vanish immediately.

In short, thoughtful, informed communication is a key part of pain care. It helps athletes maintain trust in their body—and in their team—through both recovery and performance.

Wrap

Competitive tennis requires resilience. But resilience shouldn’t mean ignoring pain or hiding it. Emerging science invites a more informed, whole-player approach. It’s not about being soft; it’s about being precise.

Pain is real. But so is the possibility of managing it more effectively when we look beyond just the physical.